Do people in creative fields have lower chances of getting dementia compared to the general population?

Rohit, I love your question, in large part because the general consensus leads to me feeling hopeful. For me, being creative (especially in music, arts, and science) has felt like the air I breathe for most of my life. Most experts have found correlations between engaging in creative, brain challenging activities and a lowered risk of dementia. And even brief reads of these studies point to how well-constructed most of them are.

My favorite studies involve retired nuns, because these women come from broadly diverse socioeconomic, biological, and cultural backgrounds. Add to this that this data has been gathered for more than three decades and is still being gathered. This makes this a highly unusual, statistically-remarkable, cross-section of people and data with which to study dementia. And yes, there are shortcomings, for example, only one gender is represented. We also cannot rule out the effects of being religious. Even so, there is much to be gleaned from reading these studies.

For instance, something that has struck me is how playing mentally challenging games in retirement correlated to a decreased risk. Whereas being multilingual, while useful as a predictor of dementia, did not decrease risk. This points to something which has yet to sufficiently surface in the conclusions listed in these studies. The missing piece? The significance of the differences between early-childhood learning and ongoing mental challenges.

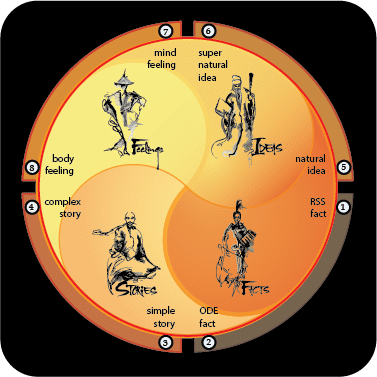

Here, it appears that to have the best chance to retain our mental faculties, we must keep using them to create new learning. Moreover, in order to see this, we must properly define the word, “creative.” In Constellated Science (see my book, the Science of Discovery, 2016), definitions must meet far stricter criteria than those of the presently accepted method. In Constellated Science, definitions must fully define “what a thing is” and “what it is not.” To do this, the scientist employs a baseline pair of complementary opposites which, by their very nature, bifurcate the data, revealing the line between these two things.

In the present case, we can accomplish this by contrasting and comparing the word “creativity” with the word “genius.” Here, genius gets defined as“the act of discovering patterns in already existing things.” Whereas creativity gets defined as “the act of destroying already existing things in order to discover new patterns.”

Now consider how this applies to health, both physical and mental. Building muscle requires existing muscle be destroyed in order to build new and better patterns of muscle. Likewise, building mental “muscle” requires that we do the same thing.

That the best results come from doing this in ways which the mind and body cannot predict; in other words, in constantly new and challenging ways, correlates to new learning. Perhaps then, new learning is the sine qua non of health? I for one think so.

Finally, something to be noted with regard to your question is that there are some 14 kinds of dementia. Does creativity affect all 14? I, for one, would like to know. Also, we have yet to discover the actual mechanism of memory. We need to know more about both of these things. This said, thank you for asking what to me is such a personally important question. No coincidence, already, this morning, I feel happier having created this admittedly incomplete response to your challenging question.