How do you explain the concept of the right and left brain to a child?

Hi Chelsea,

First, thank you for asking what to me is an intriguing question. Oddly, it seems, the responses you’ve gotten find the question irrelevant. I myself find it quite interesting. So while you haven’t mentioned the age of the child, for the sake of offering an answer, I’m going to assume she or he is at least 8 or 9.

Why does the child’s age matter, beyond the obvious?

Because children under age 8 or so have yet to learn to tell watch, clock, and calendar time. And despite the previous answers claiming any differences are irrelevant, when it comes to understanding how we sense time, the idea that our cranial brains are physical divided into two “halves” is especially important.

Unfortunately, explaining this in detail here is beyond the little space allowed. This said, I’m going to try to offer an adult answer for you, and a child’s answer for the child.

The adult answer? It begins with the idea that all adults are capable of sensing time in two ways.

The first way we sense time is as the “present moment.”

The second is “time over time.”

In the first sense of time, a moment can refer to “now,” or to “yesterday,” or to any time our brains can imagine. The point is, regardless of what time period this moment exists in, in our first sense of time, we process only one moment of it at a time. Here, recalling more than one moment is a close-to-random-access, nonlinear process. In other words, when we sense time this first way, the historical order of these moments doesn’t exist. Rather, the only time that has ever existed is the moment we are currently accessing.

Know that we’re all born in this mind-state and stay there until we learn to tell the second kind of time. This makes experiencing life incredibly alive, vivid, and personal. This first kind of time is the time of the mediator, the artist, the musician, the painter, the creative genius, and the athlete. It’s also what makes children’s needs feel so immediate to them. If they don’t get what they need now, it feels like they never will.

All this changes at around age 7 or 8 when we learn to tell watch, clock, and calendar time. At which point, we begin to see “time over time,” the kind of time that has a past, present, and future. This is the time of the planner, the accountant, the historian, the logician, the law professor, and the detective. Here, the order of the moments becomes incredibly important. It tells us how best to get what we want, or avoid what we don’t want.

Realize, developing this second sense of time is critical to our ability to answer “logical” why questions. Only then can children understand cause and effect, logical reasoning. This is why parents of children younger than 7 or 8 should never demand to know “why” this child did something. This “why” demands a logical answer from a child who cannot yet grasp logic.

Asking a young child this kind of question is cruel.

Know that being asked these “logical” (as opposed to “natural”) why questions is what programs adults to feel anxious whenever they don’t know the answers to things. Ah, if only parents got taught this before they made these demands on their children. This aside, what the heck does any of this have to do with explaining the brain to a child?

This second sense of time exists only because we have a divided brain.

Conversely, we have the first sense of time only because of the brain tissue which exists in the enteric nervous system. This brain is not divided. Hence, the first sense of time. Obviously, this is the part for which there is currently not enough room to explain. But if you’re curious, I’ve written a whole book about this.

What of the child’s explanation?

Ask the child to pick up a glass of water and drink it with their right hand. Tell the child to pay attention to how doing this feels. Does it feel natural or odd? Ask the child to try to notice.

Now ask this child to do this same thing with their left hand and ask them to notice what doing this feels like. Obviously, regardless of the child’s handedness, these two experiences will feel different.

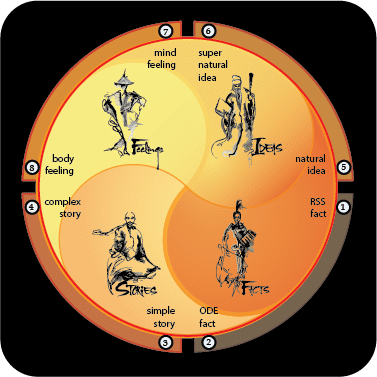

Now show the child a picture of the two halves of the brain. In particular, have the child literally point to the tiny “bridge” between these two halves, the corpus callosum.

Now have the child hold the glass with two hands and drink from this glass. Ask the child to notice what doing this feels like. Now suggest to the child that like doing things with two hands, these two parts of our brains must work together to get things done. So while adults often argue as to how, and how much, these two halves are or aren’t different, tell the child, this doesn’t really matter. All that matters is knowing that while there are differences, these two halves must learn to work together.

As do different people with different opinions.

As do adults with their children.