Is Philosophy a Science?

Once upon a time, science and philosophy were married. During this time, all scientists were generalists and called themselves, “natural philosophers.” They believed that to adequately explore the natural world, they needed a broad swath of knowledge. And that to acquire this knowledge, they needed to cooperate with, and share their discoveries with, each other.

Know this group is large; Bacon, Descartes, Heisenberg, and Einstein all referred to themselves this way. But as western science gathered more and more data, this marriage began to get rocky. Physicists stopped limiting their work to physical things. Mathematicians claimed they were the only true science. And philosophers so rose into the clouds that nothing they said made sense to science.

Eventually, this led to the end of the era of scientific generalists, as the sciences broke into smaller, more specialized groups. Along the way, philosophers did their share to wreck this marriage as well. For example, in the 17th century, David Hume posed a question science has yet to answer. He said we can never actually see cause and effect; that we assume we can see it only because one thing precedes another. An ancient Latin saying even warns against doing this; post hoc ergo prompter hoc. Despite these objections, to this day, science solves this problem by pretending it doesn’t exist.

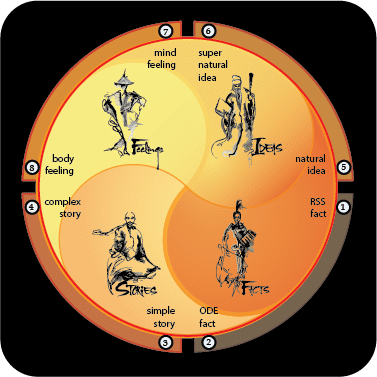

Another philosopher who did much to wreck this marriage is the early 20th philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein. His scathing work on the inadequacy of words undermined anything science could say. What does it mean when we say something is a “fact,” or that something is “real?” Indeed, in the 1930’s, Ludwik Fleck’s monologue, The Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact, raised this objection quite clearly. Science’s response? It didn’t know how to respond. So it began to pretend philosophy doesn’t exist.

My point? By the mid-twentieth century, scientists increasingly worked in more and more isolated groups. Competition for money and resources then led to today’s pathologically secretive coveting of specialized knowledge. To do this, science has had to treat the world as something knowable by the sum of it’s parts, when in truth, nature is knowable only when seen as a deeply mysterious, infinitely beautiful collaboration of emergent properties. Or to answer the question more directly, a science without philosophy is like a skeleton without flesh. You can forever examine the parts in fine detail and still, you will never understand life.

[ For a novel solution to the scientific “fact” problem, see Making Changes (the science of how ahas affect health, healing, human nature)]