If I have Asperger’s, does that mean that I am autistic?

To answer your question, I’ll need to offer a non-medical definition for the word, “autistic.” Before I do, start with this.

Nelson, please do not trouble yourself with medical labels. Most DSMs (e.g. diagnostic manuals 1 thru 5), in their prefaces, admit to and apologize for the inadequate way they assign these labels. So while the well-intended answers you’ve received here try to ease your confusion by literally answering your question, ultimately, literal answers cannot help the mind nor ease the heart. Why? Because medical labels separate (them and us), evaluate (good and bad; healthy and broken), and eviscerate (tear us apart inside, because we do not walk and talk like neurotypical normals).

You are a person.

The rest is the small details.

When I first realized (in 1991) that I had Asperger’s, I felt the need to apologize to each and every soul for what was then being described as gross insensitivity to others. At the time, I was a young therapist and had purchased a book about “high-functioning” autism. I’d hoped it would help me to help a young man who’d been diagnosed with Kanner’s Autism.

From the first page though, and page after page, what I read described me. At the time, this felt both painful and relieving. I’d found others like me and this made me feel less alone. But we were said to be broken and this hurt.

Twenty-five plus years have passed and I’ve long stopped apologizing for having what I now see as one of the four “minority personalities.” I am not broken. I am different. And this difference gives me both disadvantages and advantages, both in social situations and as a therapist.

More important though, I’ve come to see the role neurotypicals unknowingly play in creating our personalities, as from a young age, they repeatedly force us to “imitate their normal.”

Try imitating how any other person walks, talks, laughs, and cries for even a few moments. Now consider how doing this for a lifetime cripples our ability to be ourselves. More than mere theory then, I’ve used this knowledge to help many people with minority personalities. In each case, I help them to learn to build bridges to socially normal people, while at the same time never once asking them to not be themselves.

In truth, and more than any other factor, this is how we get to be different. What start out as small differences become magnified over time. This pressure to imitate normal costs us our ability to be ourselves. And anyone unable to be themselves will look and act socially awkward.

So What is “Autism?”

Forgive the technical voicing here. I do, after all, have Asperger’s (and my special interest is describing human nature).

What then is “autism?”Autism is a word which refers to people with “a personality-sized set of differences. Functionally, these differences evolve into a pervasive category of socially disconnecting distractions.“

The principle symptom? The profound inability to connect to socially “normal” people. Here, “normal” refers to a statistical rather than a medical difference.

The principle behavior? Compulsively focusing on things other than personal relationships at the expense of personal relationships. Avoiding these distractions takes precedence over learning to connect to people.

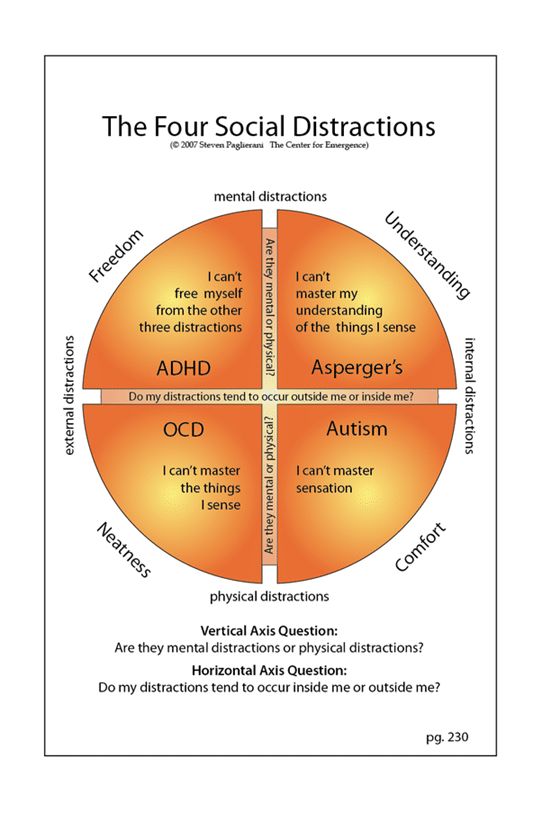

Here, there are four categories of personality-sized distractions:

- Kanner’s Autism (the distractions are unmastered, physical sensations. Origin: birth to age 6 months).

- OCD (the distractions are that the things being sensed are imperfectly arranged. Origin: 6 months to age one).

- Asperger’s (the distractions are imperfect meanings being assigned to the things being sensed. Origin: age one to age two).

- ADHD (the pressure to master anything, especially the previous three categories of distractions; the “inability to freely be social” distracts. Origin: age two to age four).

My point?

First, by this definition, all four of these minority personalities are a kind of autism. More important though, all four of these categories of distractions were once normal responses to life. Continuing to experience them outside of the usual developmental age causes them to surface at abnormal times and in abnormal ways. Here, by “abnormal,” I again mean statistically different, rather than medically broken.

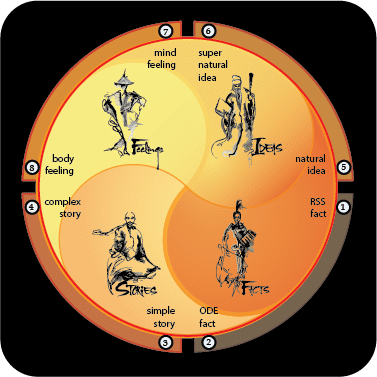

Finally, at the risk of overwhelming you even more than I suspect I have, here’s a logically geometric drawing which shows how these four personalities connect. Note how according to this way of defining the four minority personalities, [1] you cannot have more than one, [2] each has a clear and certain way to be identified, and [3] logically, these four minority personalities are all there is. There cannot be more than four nor less than four. Distraction is the key. Ask yourself by what and how often you are distracted.